Data centres are playing a pivotal role in delivering the current technological and global connectivity revolution. They contain the infrastructure responsible for the storage, processing and distribution of data, which is transforming all aspects of modern society, from healthcare to ecommerce, manufacturing to transportation.

Their importance is only going to increase thanks to the rise in digitalisation across global industries, along with the demand for advanced computing capabilities, and of course the rapid expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies.

Despite JLL reporting projected growth rates of 15% within the sector they, and many commentators are saying, there is insufficient capacity within the sector to meet demand and deliver the potential that is believed could exist within AI. More data centres are urgently needed, while existing facilities need to be upgraded to manage AI workloads.

As a result, billions of dollars are being invested in the sector, particularly by the major players who are coming out in support of AI as the technology of the future. Microsoft alone is reportedly planning a $74 billion capex in FY 2026. The company reportedly bought 485,000 Nvidia Hopper chips in 2024 and has begun rolling out its own Maia chips, installing 200,000 units in 2024, with other global tech companies following suit.

But expanding capacity is complex and protracted process. Data centre builds are capital-intensive, long lead time projects. It’s currently estimated a new 100,000 GPU AI build can cost around £6bn, taking between one to three years to construct. Developers and investors are faced with multiple barriers, ranging from a lack of available

land to labour shortages, planning delays, restrictions on the availability of local energy supplies, and lengthy

infrastructure supply lead-times. Currently, these lead-times are estimated at between 6-10 months for everything from switchgear to prefab skids.

New build costs are rising, with demand shock around the supply of major infrastructure, power, and chip systems fuelling significant price inflation.

Non-hyperscale data centre lease operators who oversee just 22% of global capacity are facing particular pressures. On the one hand, they need to invest in upgrades to their facilities to accommodate fast-changing customer needs, particularly around AI workloads to attract tenants. On the other, they need to deliver returns on their investment - which largely means being able to accurately predict the future needs of the sector and planning ahead.

However, the speed of change has exposed major gaps in existing installations which need to be plugged reliably and affordably. The good news is that we are already seeing how the sector is responding to this pressure by developing innovations that should allow data centres – and particularly data centre lease operators - to expand their operations quickly, affordably and with the least possible disruption.

How do AI Workloads Increase the Pressure on Data Centres?

It’s easy to see how AI workloads have increased the pressures on data centres, driven by their huge energy demands, requirement for enhanced cooling systems and the need for greater network connectivity.

For example, training generative AI and large language model requires vast amounts of data and large neural networks. The process depends on substantial bandwidths and immense processing power, as well as enormous memory, rapid connections between network devices (ie. switches, access points, and routers), and storage capacity. But it’s not just the training that is power-heavy. According to a recent Goldman Sachs report, a single ChatGPT query uses nearly 10 times the energy required by a Google search.

All this has meant that power consumption in data centres is rising – an issue that is a growing concern for operators given that much of the cost of running a data centre is the Energy bill. In 2024, the IEA estimates global data centres consume around 415 TWh (terawatt-hours) of electricity – approximately 1.5% of global use. By 2030, that figure could more than double to 945 TWh.

This increase has largely come about following a switch by operators from a reliance on central processing units CPUs, to greater use of graphics processing units (GPUs). GPU chips, with their parallel processing capabilities, are now routinely deployed for training Gen AI, powering machine learning, high-performance computing, scientific simulations, and data analytics. Power consumption levels of GPU servers are rising, which in turn will push up the energy demands of individual racks. While a standard rack uses 7-10 kW, an AI-capable rack can demand 30 kW to over 100 kW, with an average of 60 kW+ in dedicated AI facilities.

Not surprisingly, data centres have placed a greater emphasis on energy efficiency in recent years. Google has reported their own highly efficient power usage effectiveness (PUE) of 1.10 across all its large-scale data centres* but the IEA suggests this strategy may only partly mitigate for such a large rise in electricity use.

Greater processing power has not just ramped up power consumption, it has also increased the need for more efficient cooling systems.

High-performance processors generate considerable heat that will damage the delicate electrical components within servers if it is not removed. But its removal has been made more difficult by a modern trend towards miniaturisation of componentry, as well as rising rack densities and smaller data hall footprints, all of which has made harder to get adequate cooling into servers, directly where it is needed.

As a result, some data centres have migrated away from relying on air cooling toward liquid cooling. The latter can increase a system’s efficiency by a considerable margin, particularly when applied using on-chip methodologies (See Cooling Systems Employed Within HACs).

Data centres have also need to enable higher speed data transfers with bandwidth requirements now between several gigabits/second, to several terabits/second. Upgrading networks to fibreoptic delivers high-bandwidth connectivity, along with the low latency required by real-time processing, while also building-in capacity to allow facilities to easily scale-up as workloads increase.

Securely delivering all this additional power, networking, and cooling into racks has led to a reassessment of some fundamental aspects of data centre infrastructure. For example, data centre lease operators typically rely on ceiling-mounted aisle containment and trapeze systems for supporting the delivery of cooling, power and network connections into their servers. But increasing the power

demand of a server can lead to a doubling of the load of the power cabling and fibre connections (see section: ‘Ceiling- Mounted Aisle Containment Systems’).

In other words, raising server density means that operators need to check whether their infrastructure can cater for that increased service load.

The Use of HACs for Cooling & Infrastructure Support

Aisle containment systems within data centres are prominent features in most data centres because they are designed to help improve the efficiency of cooling systems.

Hot aisle containment (HAC) is designed to ensure that the exhausted hot air from the back of server racks does not mix with colder air that is being pumped from the chiller. The separation of the two is achieved usingoverhead panels and end-of-aisle doors that effectively seal- in, or encapsulate, an aisle.

Maintaining an effective separation with little, if any, leakage helps a data centre achieve an efficient PUE rating - the industry standard for aisle containment is a maximum leakage of 3%.

By maintaining the effective separation between hot and cold air, aisle containment systems can substantially improve the delta T (ie. the efficiency rating) of any cooling equipment. Aisle containment allows more IT equipment to be stacked higher and effectively increases the loading capacity to 10-12kW.

Higher stacking also means that operators can house more servers within the same space, thereby reducing the overall data hall footprint as well as lowering operating costs.

Cooling Systems Employed Within HACs

It’s estimated that around 8/10 data centres currently employ

air cooling as their preferred method of climate control within their server racks.

Air cooling uses hot air plenums that are created using false ceilings, into which passes the waste hot air from the servers. The hot air travels through the ceiling void and is piped to a computer room air conditioning (CRAC) unit, which cools it. The chilled air is then delivered to the data hall via Computer Room Air Handlers (CRAHs) or CRAC wall units.

But as previously indicated, air cooling has its limitations particularly as rack densities increase, AI workloads intensify, and processing power rises. So, these systems are gradually being replaced in many facilities by liquid cooling.

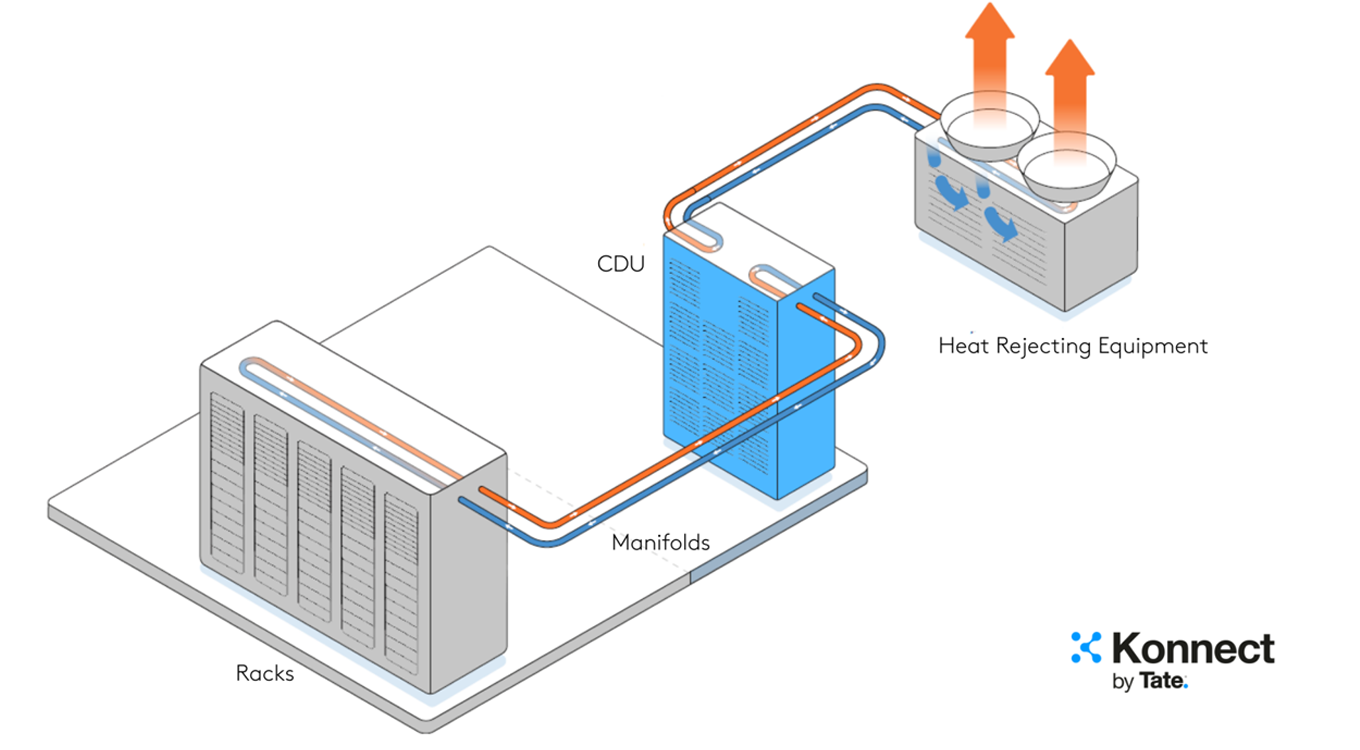

Liquid cooling takes the chilled air right into a rack through pipes known as manifolds, meaning the cooling is directed exactly to where it is needed, making it highly efficient. This means that liquid cooling can lower a data centre’s carbon footprint while its easy scalability can support any future expansion.

Liquid Cooling System

Nvidia is one manufacturer that is now designing its next-generation servers around liquid cooling to better manage the heat generated by both its CPUs and GPUs.

The next generation of liquid cooling includes direct-to-chip cooling systems which provide the most effective coolant delivery, suited to the highest density rack applications. Here, the liquid coolant is pumped through the manifolds directly to the chips, where it absorbs and removes the waste heat.

On-chip cooling further reduces the energy consumption within a rack, while optimising the environment for the servers inside. Ensuring that delicate electrical componentry is kept within its optimum temperature range means that servers can work more effectively and reliably, improving a data centre’s processing capacities and its overall uptime.

Ceiling Suspended Aisle Containment Systems

Over recent years, there has been an increased interest in floor mounted HACS to minimise the loads imposed onto the main building structure. These are often favoured where an operator requires significantly increased loads and are aware of these far in advance.

By contrast, ceiling suspended HACs are a popular option

for data centre lease operators. They give more flexibility around rack layout changes and maximise floor space.

Ceiling-mounted HACs use trapeze systems which are directly attached to the ceiling to support busbars, cable trays, fibre runners, liquid cooling, wiring and cabling, directing all these services along the aisles and above the server racks.

What’s more, while operators need to follow manufacturers’ guidelines on load tolerances, there are systems currently on the market that can carry the additional weight created by GPU-server power cables, busbars, cooling and fibre runners, with capacity to allow for future upgrades.

Clearly, as we’ve indicated, not every product can provide the same levels of support. But these tolerances are not the only consideration during any planned upgrades and should not be considered in isolation. Operators need to consider both the structural ceiling and hot aisle containment systems as a cohesive solution rather than individual components.

This holistic system approach considers the ceiling, HAC, and liquid cooling manifolds as a single integrated system, ensuring better efficiency, stability, and scalability while also enabling readiness for future advancements.

In other words, data centre lease operators who plan to raise the server density within their existing racks (perhaps while installing GPU servers) should also ensure they have confirmed the structural integrity of not just the HAC, but also the ceiling and the building substructure above it.

Both elements need to be rated as capable of carrying the expected increased loads, even as these vary. For example, the fluid within the liquid supply and liquid return manifolds required by liquid cooling packages will expand and contract. Thermal fluid dynamics means it also vibrates, and this creates an extra loading pressure that needs to be accounted for. So, while it may be possible to add a few individual services piecemeal to a trapeze system, operators need to consider the collective impact of all the new cabling and manifolds before authorising any server upgrades.

By designing-in infrastructure that is already able to take predicted future loads, operators can avoid the need

for regular replacements/retrofitting, hence why this is recommended as part of the build design mindset.And there are significant benefits to working with only one manufacturer. These include ensuring component compatibility to help simplify installation and reduce the risks of misalignment. Again, this minimises complexities by ensuring that all parts of the system work seamlessly together without the need for adjustments or modifications.

An example of this is a type of a ceiling- suspended HAC system with gantry arms, all of which is attached to a heavier duty structural ceiling. The system’s cantilever arms take the place of the trapeze sling in providing support to the services going to and from the servers. The new HACs have a very high load specification, compared to other ceiling-mounted products, as evidenced by the Tate Forte LEC Hybrid Gantry HAC which can support a point load of 4.4kN.

The Future

It’s clear that the demand shock created by the AI revolution has led to a massive deployment of resources by data centre operators and others in the supply chain to deliver the required infrastructure within extremely tight lead times.

Achieving AI’s potential (whatever that might be) depends on having data centre infrastructure that can support its exceptionally high workload. But supply chain bottlenecks are slowing the rate of progress.

Data centre cultures that embrace agility, responsiveness, and flexibility are likely to put the respective companies at an advantage in this space, because the future remains very uncertain, while the speed of change is fast.

For example, data centre lease operators who can quickly adapt their existing facilities to meet the overwhelming demand will achieve significant competitive advantage and will be less affected by supply issues. Just as importantly, operators need to manage the costs of any future expansion and keep investment levels to a serviceable level, even as demand drives infrastructure prices up.

While all this is a reflection on the market’s current trajectory, we cannot ignore sector innovations that could be just as decisive in determining AI’s future development path. For example, we are seeing the evolution of new infrastructure (such as a vertical integration of your structural ceiling and HAC system, with added gantry arms) that will instantly add capacity and give data centre lease operators the flexibility they need to meet any future power, data, and cooling demands posed by GPU chips.

Furthermore, in time there may also be greater pressures directed towards chip manufacturers from global industry leaders (and possibly governments) to encourage chip suppliers to develop solutions that require lower energy levels and produce less heat.

If this happens, the industry may need to adapt once again, swapping liquid cooling packages in a return to large, air- cooled, and less-expensive-to-build data centres.

For more information on liquid cooling and data centre infrastructure solutions, schedule a collaborative workshop below.

In today’s evolving landscape, we are uniting power, cooling, and connectivity to drive your AI-ready data centre into the future.

Click here to learn more about Tate Konnect.